The other day I was talking with Desiree Schell about activist stunts. What makes one stunt an effective protest action, and another a placebo protest (in Tribal Science author Mike McRae’s memorably pointed phrase)?

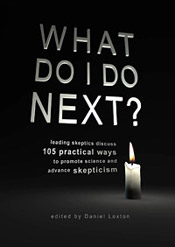

This 68-page PDF brings together 13 leading skeptics for a panel-format discussion of skeptical activism

As skeptics consider skeptical activism (perhaps using some of the ideas described in this 68-page PDF panel discussion, or this point form version), what steps can we take to maximize the impact of our hard work? How can we make the best use of our limited resources? And, how can we avoid the trap McRae describes: “outreach efforts that have no real prior goal other than a vague sense of improvement in the public’s awareness of how silly something sounds and how sensible science must be.” (I give more weight to awareness campaigns than does McRae, but his point about goals is well taken.)

Desiree Schell is the person to ask. She’s well known as the host of Skeptically Speaking (a live radio talk show carried on dozens of stations, also released as a podcast), but it’s her day job that makes her a relevant expert: Desiree is a professional union organizer. Not only has she organized dozens of marches, rallies, protests, and other direct actions, but she literally teaches courses instructing other labour organizers about effective direct action strategies.

Schell shows her classes this YouTube video, in which a hotel boycott is announced by a musical flashmob, as an example of a well-conceived action. It is inherently telegenic, applies strong economic pressure (targeting San Francisco hotels during Pride), and neatly heads off potential backlash. Smart. (Schell asks her students, “Why do you think they used the phrase ‘I want your gay ass?’”)

I anted in a favorite example of my own: this 2009 YouTube video seen by almost ten million people, in which Canadian country musician Dave Carroll expresses dissatisfaction with the customer service of United Airlines. Check it out, and then we’ll talk about the strategies it embodies.

This video (along with its amusing sequels, here and here) garnered massive press. Carroll was featured by leading networks and newspapers worldwide — as was his message. The song “United Breaks Guitars” shot to the top of the iTunes charts, while Time dubbed it one of the “Top 10 Viral Videos” of 2009.

The Times of London argued that this press had a correspondingly massive real world impact: “within four days of the song going online, the gathering thunderclouds of bad PR caused United Airlines’ stock price to suffer a mid-flight stall, and it plunged by 10 per cent, costing shareholders $180 million.” Other commentators countered that the stock price drop was a coincidental part of a downward trend — but agreed, “The damage to United’s brand was undeniable.” The chairman of public relations giant Weber Shandwick described it to Forbes as “the worst case scenario.” CNN’s Wolf Blitzer solemnly intoned, “They should have just bought him a new Taylor guitar, and that would have been it. But it’s a good song. … I like that song.”

Under such intense public relations pressure, United eventually met every item on Carroll’s list of demands: they apologized, offered money, and pledged to improve their customer service. (They planned, wisely, to use Carroll’s video as part of their internal training.)

Before unpacking the structure of this cheeky protest stunt, I’d note that this is certainly not the only model that skeptics might learn from. Indeed, the heavy lifting in skepticism does not involve activist stunts at all, but research and education. As well, ethical considerations make skeptical activism particularly complex — and may severely constrain the approaches available to skeptics.

That said, let’s break down some of the strategies employed by “United Breaks Guitars”:

1 Picking a specific target that is vulnerable to pressure. Carroll’s target is not “jerks behind desks” or “the airline industry,” but United Airlines in particular. Abstracts are not vulnerable to protest pressure, but companies are. Likewise, professional organizations, government administrations, politicians, and media sources can all be influenced by the carrots and sticks available to activists: brand enhancement, boycotts, scandal, praise.

2 Speaking directly to a specific audience. Carroll’s intended audience may be large, but it is also specific: YouTube users who travel by plane. The video is well-designed to appeal to the widest possible subset of that YouTube audience: it is light, entertaining, and specific to airline travel. There is no distracting or extraneous material. We don’t hear about Carroll’s other causes, his hobbies, his politics, his religious beliefs, or anything else that might sub-divide his audience.

Skeptics struggle with this. Who are we trying to engage? Veteran skeptics? Pop science fans? The general public? Those committed to deeply-held paranormal beliefs? The truth is that no message speaks to all audiences — and indeed, engaging one may often alienate the others. To get a sense of how challenging this can be, I strongly recommend former New Age author Karla McLaren’s famous Skeptical Inquirer article “Bridging the Chasm between Two Cultures.” She argues passionately that the style of skeptical communications conceals the value of skeptical information, making it nearly impossible for people in the New Age culture to hear what skeptics are saying:

Why do I (the sort of person who actually needs skeptical information) have to see myself described in offensive terms and bow my head in shame before I can truly access the information available in your culture? … I would ask you to approach us as fellow humans who share your concern and interest in the welfare of others. I would ask you to be as culturally intelligent as you are scientifically intelligent, and to work to understand our culture as clearly as you understand the techniques, ideas, and modalities that have sprung from it. We are a people, not a problem.

3 Focussing on a specific issue — not general antagonism. There may be a million things Dave Carroll dislikes about United, air travel in general, or American capitalism — he doesn’t tell us. His stunt spotlights a single complaint: he was failed by United Airlines’ customer service. The power of his message comes from its simplicity. (I can’t even remember if I’ve ever flown United, but thanks to Dave Carroll — fairly or not — “crappy customer service” is the only impression I associate with the brand.)

Focus is useful. I’m reminded here of the plot of the film Inception, in which the protagonists try to implant an idea in another person’s mind: the simpler the idea, the less resistance to overcome. If we double the size of the pill, we halve the number of people who can swallow it. With any given message (“vaccines save lives”) we can aspire to X amount of support; when we multiply our claims (“vaccines save lives, and also public schools should be abolished / God is the source of all goodness / Kirk is better than Picard”) we divide that support with each added claim. Package enough positions together, and the only people sympathetic to our message will be those few who already agree.

4 Clearly stating a call to action. Carroll is very specific about the actions he wants United to take:

You broke it; you should fix it. You’re liable — just admit it. … To all the airline’s people…I’ve heard all your excuses and I’ve chased your wild gooses, and this attitude of yours I say must go.

That is, apologize, pay up, and fix customer service. To motivate United to take these concrete steps, Carroll also hammers away at an implied call to punitive action for millions of United customers: fly with someone else, or go by car.

5 Positioning the protester as the Good Guy. A protest can be viewed through competing narrative lenses: either as an exercise in standing up for what’s right — or as bullying, whining, self-indulgent extortion.

Carroll takes firm control of his own story, positioning himself as a nice guy shining a good-natured light on a heartless bureaucracy for reasons of basic human decency. His message depends upon his persona, which the The Times of London describes as a “ruffled, likeable, almost-handsome everyman who could star in his own Hollywood romantic comedy.” While Carroll may also be a sweet guy in real life, the practical point is that he portrays one on TV (or rather, on YouTube).

If audiences had viewed Carroll in a less favorable light, his protest stunt would have failed. Think about how easily this same story could be read as a tantrum: “His luggage got damaged. So? Most luggage arrives in perfect condition, but we all understand when we board that there’s a small chance of handling damage. The case was investigated through the airline’s standard procedures, and resolved. This is some sort of international scandal? Lose perspective much?” (I’ve stood behind complaining airline customers and had just such thoughts. C’mon, lady, there’s a line here.)

Activists should avoid being backed into corners where they can be re-cast as the villains. It’s easy to stumble here. The protester is the one taking up the audience’s time, the one raising a criticism. The burden is on us to explain why our message deserves to be heard. In the meantime, critics may seek to paint skeptical activists as shills, bullies, ideologues, “pro-vaccine-injury bloggers,” or the like.

To be most effective, skeptical activists should be prepared to pre-empt negative characterizations. Our best chance to control the optics surrounding activism is to always genuinely take the high road. Have a fair position. Have command of the facts. Stay within the law! Don’t exaggerate. Be charitable with opponents. Be prepared to praise positive progress.

For more on the importance of accuracy and fairness in criticism, I cannot recommend more highly the 1987 article “Proper Criticism,” by founding CSICOP member Ray Hyman. It is an essential document which all skeptics should study (and indeed, it has long been used as an internal editorial policy document at the Skeptical Inquirer). Please do read it.

6 Achieving decent production values. Carroll’s music video may feel folksy and homegrown, but that impression is misleading. The video owes its success in large part to a snappy tune, high-quality audio, and great comic timing — and it pulls that off because it is written and performed by professional entertainers.

Competing in the marketplace of ideas is tough. To reach that bar takes hard work, and sometimes requires professional expertise.

Speaking of Professionals

When I was writing this post, Desiree Schell kindly showed me the outline for her Direct Action course. It’s 53 pages long! As in related fields (marketing, education, science communication) there’s clearly a lot to learn.

Does this mean that grassroots skeptics should be frozen into inaction? I hope not! The complexity and ethical stakes of skeptical activism give us reason for care, clarity, compassion, and planning — not paralysis. Along the way we’ll stumble now and again; but, if we welcome positive criticism, we’ll learn. And we’ll help people.

We need your ass out there. Gay or otherwise.

"

No comments:

Post a Comment