"If I'm not grounded pretty soon, I'm gonna go into orbit."

-- Warren Oates A.K.A. GTO

It feels almost too easy applying the term “existential” to Monte Hellman’s mysterious Two-Lane Blacktop, (and Mr. Hellman has always insisted that the picture is not “existential”) but I think the alienated, ambiguous, weirdly funny and, at times, desultory cult car classic deserves the appellation. A work of stark Sisyphean power, the picture brilliantly combines automobile allure and the expectations of the race with a sparer saga of the road -- a road that should be free but isn’t free at all.

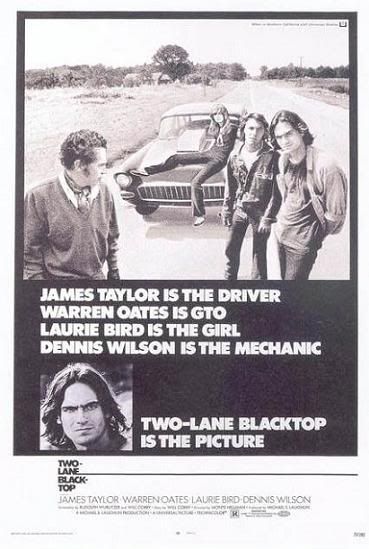

This may sound rather joyless for a car movie, and indeed for the greatest car movie ever made, but the picture is so inventive, so austerely beautiful, so unexpected and so gorgeously auto-centric, that it’s a singular wonder. With a then much discussed script by Rudy Wurlitzer, the movie came heaped with an interesting amount of hype. The screenplay managed the honor of being featured on the cover of Esquire Magazine before the film was made, something that was unheard of at the time, and something that made the movie’s lack of box office more of a disappointment. Naturally, it’s been a cult favorite ever since.

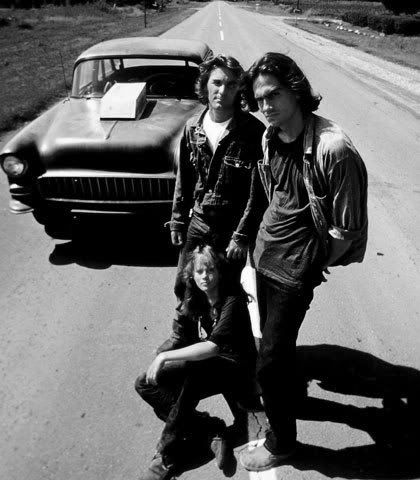

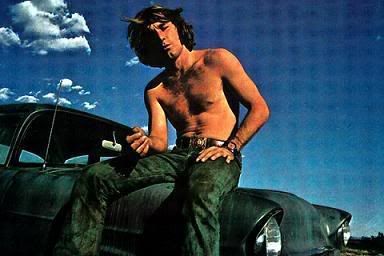

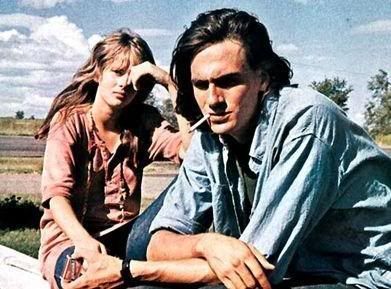

Leading this gear-head mediation through its long stretches of lonesome highway are characters stripped down to their basic handles -- James Taylor is known only as the “Driver,” Dennis Wilson the “Mechanic,” Laurie Bird the “Girl” and the late great Warren Oates, in one of his most unforgettable roles, is “GTO.” The stoic Taylor and Wilson work a seriously souped-up '55 Chevy that's all muscle and speed, no frills, while a garrulous Oates rolls a yellow 1970 Pontiac GTO -- something Taylor scorns as right off the lot. All players endlessly drive, seemingly to challenge other cars and race cross country, but who knows what they’re really seeking. When somewhat challenged on the matter -- that all the speed will burn him up -- the Driver famously replies “You can never go fast enough.” And the picture doesn’t spare this feeling on the viewer as the continual purr and hum of the engine places you at one with the car -- a oneness that has become the character’s very identities.

Two-Lane Blacktop was probably supposed to be a youth movie, but there’s nothing young about it. Taylor, Wilson and Bird, though certainly not adults (in the conventional sense of the word) nevertheless carry a heavy amount of resigned cynicism within their cipher, stoic, underfed, frames. Had the movie been made in the 1960s, we might have gotten that kind of hip-swiveling, gone daddy-o, Psych Out energy (think Mimsy Farmer tripping on drugs in Riot on Sunset Strip) but Two-Lane isn’t working on that tip -- these people, whether they know it or not, are representative of their era -- their specifically 70s era. The rather glamorized late 60s -- the so-called free, hippie-flower-child-dancing, politically motivated and finally, tragic decade crashes directly into this Lane, where inspiration comes not from changing the world but from … cars. Which makes perfect sense to me -- if you can control one thing during such chaotic times (and if you desire anything to represent freedom) -- it’s your automobile.

As such, these gear-heads aren’t driving for show, they’re not trying to pick up chicks (though Bird casually crawls into their car, which they barely acknowledge) -- they’re simply driving (and driving), with uber serious, monk-like intent. Interestingly, it’s overly energetic Warren Oates who represents the “youth movement” an ultimately lonely and dissipated man who thinks that maybe he can understand the kids but is frustrated by their abilities (He doesn't appreciate being crowed through two states by a couple of two bit "road hogs" he complains to the boys). He’s full of half truths, or flat-out- fantasies, and we wonder about his life -- did he dump a middle class existence and family to head out for the open road, like those all those hippies he’s seen cruising the streets or traipsing around those acid-soaked youth movies? What's with this guy? Is he having any fun? Not really. As such, he’s something of a freak -- not some older road tripping cool guy, but in the end, a mournful man (though looking at his bad-ass GTO now only makes me pine for the days when cars like that really did roll off the lot, instead of these modern suppositories). And we come to pity him, even care about him -- more than the other characters. After all, they have youth on their side. But there's that idea of "youth" again. Does their youth really matter? Though conformity may represent the soul sucking void to them, it’s possible that getting lost isn’t what it’s cracked up to be either. Gaspar Noe could have titled this film, because these "kids" are enterting it.

But this isn’t to say the picture’s depressing, it’s also quite funny and in its subtle moments, charming (Oates, whom I revere in every movie he’s ever made, displays a fantastic amount of mysterious weirdness and pitch perfect comic timing). Two-Lane Blacktop is, no question, a work of enigmatic significance and auto-erotic gorgeousness.

Unlike any other car picture (and I love a lot of them) Two-Lane Blacktop sits or, more appropriately, drives in a class by itself. It zooms far past those three yards a drawling James Taylor spits out before a racing challenge, but his assuredness matches the perfection of the movie: “Make it three yards motherfucker and we’ll have ourselves an auto-mo-beel race.” A race that never ends. Which, car or no car, just might be the ultimate challenge.

Two-Lane Blacktop plays tonight, at 7:30 at LACMA. Monte Hellman will be there to discuss his masterpiece.

No comments:

Post a Comment